African Civilisational Architecture

Mapping African knowledge and memory through cycles of resilience and renewal

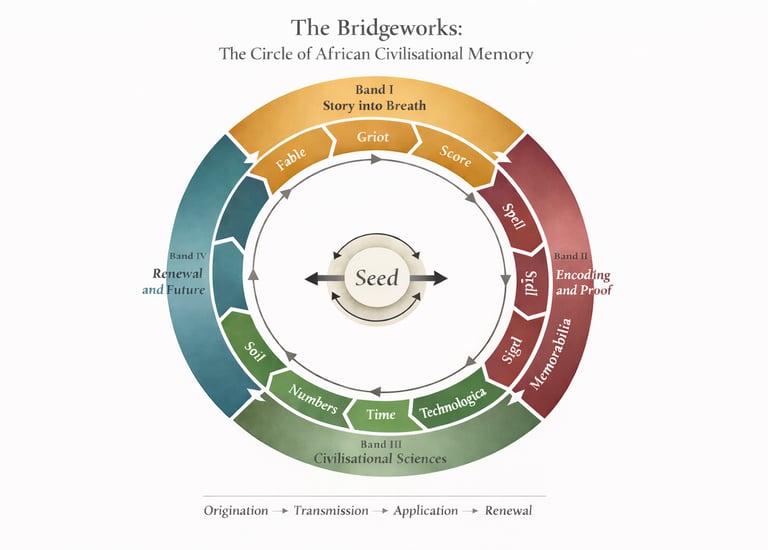

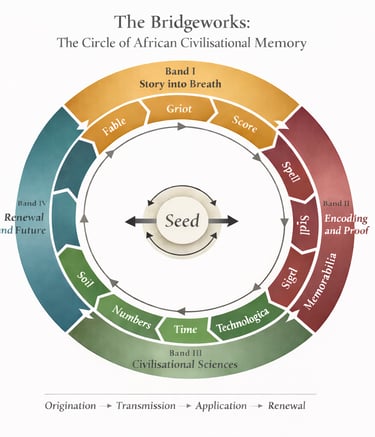

"The Bridgeworks"

A living architecture of African memory and knowledge, weaving continuity through rupture and erasure.

A Civilisational Architecture of African Knowledge and Memory

Continuity and Rupture in the Black World

This work sets out a civilisational architecture of African knowledge and memory, concerned with continuity and rupture in the Black world. It describes the underlying structures through which African civilisations generated, preserved, transmitted, applied, and renewed knowledge across time, including under conditions of extreme disruption.

This architecture is referred to here as The Bridgeworks. It is a civilisational grammar and epistemic architecture for knowledge survivability under erasure.

Without stating so explicitly, this framing accomplishes several things at once. It establishes rupture as the condition rather than deficiency. It positions Africa as the designer of survivability rather than the victim of loss. It signals method rather than content. It refuses folklore, nostalgia, and identity politics as explanatory frames. It presents the work as transferable rather than personal.

This work proceeds by identifying civilisational architecture as a primary analytic level, rather than treating African knowledge as content to be recovered or traditions to be compared.

What follows is an account of that design.

The Bridgeworks

Civilisations do not disappear because they lack knowledge. They disappear when the mechanisms that carry knowledge across rupture are broken, discredited, or erased.

African civilisations understood this long before the catastrophic ruptures of enslavement and colonialism arrived. They designed knowledge systems that assumed disruption, not stability. What they could not foresee was the sheer scale - the totalising violence of forced displacement, the deliberate destruction of archives, the criminalisation of memory itself. But what they did foresee, and what they prepared for, was rupture as a condition of existence.

Ruptures They Anticipated

African societies faced recurring pressures that threatened knowledge continuity:

Environmental disruption - Droughts, floods, and climate shifts that forced migration and displaced populations from their lands. Knowledge tied to a single location would not survive.

Political instability - Wars, conquests, the rise and fall of kingdoms. Power structures could collapse. Institutions could be overthrown. Archives could be seized or burned.

Generational fragility - Death, whether sudden (war, disease) or natural, meant that knowledge held by individuals alone would vanish. Elders could die before transmitting what they knew.

Social fracture - Communities could split. Lineages could scatter. Exile, whether voluntary or forced, was always possible. Knowledge had to travel with people, not remain locked in places.

Linguistic change -Languages evolved, diverged, and transformed through contact which meant that knowledge encoded in a single tongue could become illegible over time.

African knowledge systems were designed to withstand all of these. They built for portability (knowledge that moved with bodies, not buildings), redundancy (multiple carriers, multiple forms), and adaptability (systems that could absorb new materials, languages, contexts without losing core structure).

What they could not anticipate was deliberate civilisational erasure—the systematic effort to destroy not just archives but the very people who carried memory. The transatlantic slave trade and European colonialism were ruptures of a different order: not natural disasters or political shifts, but ideological programs designed to sever African peoples from their pasts entirely.

And yet, the architecture survived. Not intact, but functional, because it had been designed for rupture from the beginning.

Why They Went to Such Lengths

The effort invested in securing knowledge across so many domains, from Fable (narrative), Griot (custodianship), Score (rhythm), Spell (performative encoding), Script (inscription), Sigil (visual compression), to Memorabilia (material proof), was not paranoia. It was realism. It was information security.

African societies understood that knowledge is civilisation, and that without memory of law, governance collapses. Without memory of ecology, agriculture fails. Without memory of lineage, social order fractures. Without memory of cosmology, meaning disintegrates.

They also very clearly understood that single-point storage is catastrophic risk. A library can burn. A specialist can die. A monument can be toppled. A language can be banned. If knowledge lives in only one form, one place, one person, it dies when that carrier is destroyed.

So they distributed knowledge across multiple, reinforcing systems:

Story could be remembered and retold even when texts were destroyed

Bodies could carry rhythm and gesture even when instruments were banned

Symbols could be inscribed on objects, skin, and ground even when writing was forbidden

Land held memory in sacred sites, even when archives were looted

Objects carried proof of continuity even when documentation was lost

Performance transmitted knowledge through repetition even when formal teaching was suppressed

The fact that each system reinforced the others, so that if one failed, the rest remained was as not accidental but architectural.

What Redundancy Actually Means Here

Redundancy can be misunderstood as wasteful or repetitious but people who work with information technolgy know that, in knowledge systems, redundancy is intentional duplication across different media to ensure archival survival.

In the Bridgeworks, redundancy operates at multiple levels:

1. Multi-modal encoding - The same knowledge exists simultaneously in story (Fable), song (Score), symbol (Sigil), and object (Memorabilia). If text is destroyed, the story persists. If objects are looted, the song remains. If performance is banned, the symbols endure.

2. Distributed custodianship - Knowledge is not held by one person but by multiple specialists (Griot) whose lineages overlap. If one lineage is broken, others continue. Communal verification means that no single authority can corrupt the record unchallenged.

3. Embodied and environmental storage - Knowledge lives not only in minds but in bodies (Score, Spell) and in the land itself (Soil, sacred sites). Memory is not abstract. It is physical, embedded in practice, place, and material form.

4. Recursive loops - Knowledge re-enters the system at multiple points, for example:

Seed returns to Fable when what has been preserved becomes instruction again.

Memorabilia returns to Griot because objects trigger retelling.

Score informs Spell where rhythm structures ritual. These internal recursions mean that even if part of the circle is broken, knowledge can re-establish itself through another path.

5. Adaptive resilience - Systems designed for redundancy are also designed for transformation. When African knowledge crossed the Atlantic under enslavement, it did not replicate exactly - it adapted. Fable became folk tale and cautionary story. Griot became preacher and rapper. Score became blues, jazz, and hip-hop. Spell became Vodou, Hoodoo, and Obeah. The architecture held even as the landscape, content and context shifted.

The Scale of the Design

What is remarkable is not that African societies preserved knowledge, but that they preserved it across so many dimensions simultaneously.

They did not choose between oral and written. They used both. Yes, written; Early Africans had Script.

They did not choose between individual and collective memory. They structured both.

They did not choose between narrative and material proof. They embedded both.

They did not choose between cosmology and science. They integrated both.

This was not belt-and-suspenders caution. This was civilisational engineering at the highest level—the recognition that knowledge must circulate through every available medium to survive the unforeseeable. And when the unforeseeable arrived—enslavement, forced migration, cultural suppression, linguistic fragmentation,archival destruction—the architecture proved its worth. Not because it was perfect, but because it was redundant.

The Bridgeworks names that redundancy and describes how knowledge moved through story, body, symbol, land, number, object, and time. It shows that what endured did so not by accident, but by design.

What follows is not linear.

It is a circle.

Band I — Story into Breath

Origination and Transmission

Civilisation begins in story, but story alone does not endure. For knowledge to survive across time, movement, and rupture, it must be carried, performed, remembered, and corrected. In African civilisations, this function was often structured and formal.

Fable marks the point of origination. It is not entertainment, nor allegory in the trivial sense. Fable is instruction encoded in narrative form. It carries cosmology, ethics, history, and law in a mode that can travel where direct record cannot. Under conditions of danger or suppression, fable allows knowledge to circulate without naming itself openly, requiring deep contextual and domain knowledge at times, to be legible.

Griot names custodianship, so that foundational, critical and civilisational knowledge was not left to chance transmission. The position of Griot was held by trained specialists whose authority derived from accuracy, continuity, and communal verification. Griotic systems ensured that memory was not merely remembered, but performed, challenged, corrected, and renewed in public settings. This was not improvisation. It was disciplined recall.

Score is the mechanism that allows story to persist beyond individual memory. Rhythm, repetition, pattern, and cadence imprint knowledge into the body and the collective. Through song, chant, sequence, and ritual timing, information becomes durable. Score transforms knowledge into something that can survive migration, enslavement, exile, and generational rupture without dependence on a single carrier.

Together, Fable, Griot, and Score establish oral intelligence as system, not absence. They demonstrate that transmission was engineered for survivability, redundancy, and correction, long before the conditions that would make such design necessary became fully visible.

Band II — Encoding and Proof

Preservation, Authority, Evidence

Knowledge that survives initial transmission must next become durable. It must acquire retain fidelity, authority, verifiability, and resistance to distortion. In African civilisations, this function was not accidental. It was achieved through multiple encoding technologies designed to fix meaning, compress complexity, and preserve memory beyond individual bodies.

Spell names performative encoding. Speech was not treated as neutral description but as action. Incantation, invocation, and ritual utterance functioned as technologies through which law, memory, obligation, and consequence were enacted. Meaning was bound to correct performance. Knowledge encoded in spell was preserved through repetition, sanction, and communal recognition. It could not be freely altered without consequence.

Script establishes inscription. African civilisations developed and maintained written systems for recording knowledge, governance, trade, cosmology, and law. These included ideographic, syllabic, and symbolic scripts such as Nsịbịdị, Vai, Medu Neter, and the manuscript traditions of Timbuktu. Writing did not replace oral systems. It operated alongside them, fixing knowledge where durability, precision, or authority required it.

Sigil compresses meaning into form. Symbols, cosmograms, marks, and geometric systems encoded layered knowledge into visual shorthand. Sigils carried cosmology, mathematics, ethics, and strategy in forms that could be recognised, reproduced, and transmitted across distance and time. They functioned as portable archives, capable of surviving where extended text could not.

Memorabilia anchors memory in matter. Artefacts, ritual objects, architecture, bronzes, terracotta, earthworks, and monuments embodied knowledge physically. They served as mnemonic devices, proof of continuity, and repositories of authority. Memory was not abstracted from the world. It was embedded in it. Objects verified what stories carried and what scripts recorded.

Together, Spell, Script, Sigil, and Memorabilia dismantle the fiction of “pure orality.” They demonstrate that African civilisations were intentional about record-keeping, verification, and preservation. Encoding was layered, redundant, and distributed across speech, text, symbol, and object so that no single point of destruction could erase the whole.

Band III — Civilisational Sciences

Application, Survival, Continuity

A civilisation does not endure on memory alone. Knowledge must be applied to land, matter, time, and number in order to sustain life, organise complexity, and reproduce itself materially. In African civilisations, this work was not secondary to myth. It was integrated within it.

Soil names ecological intelligence. Land was not treated as inert resource but as living system requiring stewardship, balance, and care. Agricultural knowledge, biodiversity management, medicinal systems, and settlement patterns were embedded within cosmology and ritual practice. Soil carried memory of cultivation, climate, and survival strategies accumulated over generations. Ecological knowledge was not abstracted from culture. It was governed through it.

Numbers represent applied mathematics. African civilisations developed sophisticated systems of counting, measurement, proportion, and pattern long before their recognition within Western canons. This included fractal geometries in architecture and textiles, complex accounting systems, and mathematical reasoning evident in artefacts such as the Ishango bone. Number functioned as both practical tool and cosmological principle, linking calculation to order.

Time refers to chronometric systems. African temporalities were cyclical, spiral, and regenerative rather than strictly linear. Calendrical systems governed agriculture, ritual, governance, and cosmology with precision. Nile Time exemplifies a sophisticated understanding of seasonal cycles, astronomical observation, and temporal coordination at civilisational scale. Time was not merely measured. It was inhabited.

Technologica names material innovation. African societies developed advanced technologies in metallurgy, textiles, architecture, navigation, and tool-making. Iron smelting, engineering works, and complex production systems demonstrate applied scientific knowledge rooted in local environments and cosmologies. Technology was not separate from myth. Myth provided the logic through which innovation was justified, regulated, and transmitted.

Together, Soil, Numbers, Time, and Technologica demonstrate Africa as engineer, scientist, and systems-builder. These were not isolated achievements. They formed an integrated civilisational science through which knowledge was tested against survival, continuity, and scale. Where Band I transmits and Band II preserves, Band III sustains.

Band IV — Renewal and Future

Regeneration and Futurity

Civilisation does not conclude with preservation or application. It must renew itself. Knowledge that cannot generate future continuity collapses into archive, monument, or museum. In African civilisational logic, renewal was not symbolic. It was structural.

Seed names stored futurity. It is the principle through which knowledge, life, and possibility are carried forward beyond the present moment. Seed holds potential in compressed form. It anticipates loss, delay, and rupture by preparing for conditions that do not yet exist. In agricultural terms, seed ensures survival beyond famine or displacement. In civilisational terms, seed ensures continuity beyond collapse.

Seed operates in direct relation to Soil, completing the material cycle, and in direct relation to Fable, reopening the instructional cycle. What is cultivated must be replanted. What is remembered must be retold. Renewal is not repetition. It is reactivation under new conditions.

This arc locates African knowledge systems as future-oriented rather than backward-facing. It rejects preservation as an end in itself. Instead, it insists on regeneration, adaptability, and sovereignty over continuation. Without Seed, the civilisational circle hardens into relic. With Seed, it remains alive.

Seed closes the Bridgeworks not as an ending, but as a return. The circle completes itself and begins again.

Directional Logic

Continuity, Recursion, Return

The Bridgeworks operates through directional movement rather than linear progression. Knowledge does not advance along a single path. It circulates. The architecture is therefore read clockwise, beginning with origination and returning through renewal, but it is also recursive, allowing knowledge to re-enter the system at multiple points.

The primary flow proceeds as follows:

Fable → Griot → Score → Spell → Script → Sigil → Memorabilia → Soil → Numbers → Time → Technologica → Seed

This movement traces how knowledge is first generated, then transmitted, encoded, applied, and renewed. Each function depends on the integrity of the others. No single codex is sufficient on its own. Durability emerges from interdependence.

The clockwise direction reflects generative logic. Knowledge moves from instruction into custodianship, from rhythm into authority, from symbol into matter, from matter into calculation, from calculation into time, and from time into innovation. This sequence is not arbitrary. It mirrors how civilisations convert meaning into survival.

The system is also explicitly recursive. Seed returns to Fable. Stored future becomes instruction again. What has been preserved and applied is re-entered into story so that the next generation can receive it under altered conditions. This recursion ensures that continuity is not static but adaptive.

Several secondary recursive relationships operate within the circle. Score informs Spell, as rhythm structures incantation. Memorabilia returns knowledge to story by enabling retelling through object and site. Soil renews Seed, anchoring futurity in ecology. These internal loops allow the system to absorb rupture without collapse.

The Bridgeworks therefore refuses linear models of progress or decline. It does not describe ascent, evolution, or replacement. It describes circulation, redundancy, and return. Knowledge survives not by moving forward away from its origins, but by repeatedly passing through them in altered form.

This directional logic is the core of the architecture. It explains how African civilisations anticipated disruption and designed knowledge systems capable of surviving it.

Implications of the Architecture

The Bridgeworks are highly consequential because it changes the level at which African knowledge is understood. It shifts the discussion from content to structure, from fragments to systems, and from loss to design. Without this shift, African history is repeatedly misread as incomplete rather than interrupted.

Much of what has been described as disappearance or absence is, in fact, the result of broken transmission mechanisms. When griotic lineages are disrupted, scripts suppressed, objects looted, land alienated, and temporal systems overwritten, knowledge appears to vanish. The Bridgeworks makes visible that what failed was not knowledge itself, but the conditions that allowed it to circulate.

Mythology, in this framework, is not treated as symbolic excess or pre-rational belief, but as a disciplined memory technology.

Fable and Griot function as early systems of compression, encoding complex social, ecological, and ethical knowledge into forms that can survive transmission without writing. These mythic forms are accountable, repeatable, and socially verifiable, making them the necessary foundation upon which later inscription, numeracy, and scientific abstraction are built.

This matters for African history because it restores authorship. African civilisations are no longer positioned as passive carriers of belief or as contributors to external canons, but as designers of complete epistemological systems. Their myths become infrastructural. Their sciences become legible. Their technologies regain continuity.

It matters for the African diaspora because it explains persistence. Cultural survivals are often treated as accidental or purely expressive. Through the Bridgeworks, rhythm, story, symbol, and ritual can be recognised as deliberate carriers of civilisational memory, capable of crossing oceans, generations, and regimes of suppression.

It matters for scholarship because it offers a method that can be applied across disciplines. History, anthropology, religious studies, science, and technology studies can engage African material without reducing it to folklore or extracting it into foreign frameworks. The architecture provides a way to see coherence where fragmentation has been assumed.

It matters for the future because it reframes continuity as a design problem rather than a nostalgia project. In a world facing ecological collapse, data loss, technological fragility, and cultural rupture, the Bridgeworks offers a model for resilient knowledge systems that prioritise redundancy, regeneration, and adaptability over permanence alone.

This is not a recovery of the past for its own sake. It is a clarification of how civilisations survive.

Conclusion

The Bridgeworks is not a metaphor and not a taxonomy. It is a description of how African civilisations organised knowledge to survive interruption. It identifies the structures through which meaning was generated, carried, proven, applied, and renewed under conditions that assumed rupture rather than stability.

African societies explicitly designed knowledge systems that assumed disruption rather than permanence.

Griotic training required decades and distributed knowledge across multiple specialists (Hale, 1998).

Ifá divination remained oral even when writing was available because "what is written can be destroyed" (Bascom, 1969).

Nsịbịdị script was encrypted by design to protect knowledge from hostile outsiders (Dalby, 1986).

Kongo cosmograms were portable because "what can be built can be destroyed" (Fu-Kiau, 2001).

Rhythm was embodied because "knowledge in the body cannot be taken" (Chernoff, 1979).

Engineering decisions, all.

Seen through this architecture, African mythology is no longer an isolated domain of belief, nor African science a series of anomalies. Both are intelligible as components of a single epistemological system designed for continuity. What endured did so because it was distributed across multiple carriers. What appears fragmented becomes coherent once structure is restored.

This framework does not argue for recognition. It establishes legibility. It does not seek recovery for its own sake. It clarifies how survival was achieved, and how continuity was engineered.

The circle closes where it began. Seed returns to Fable. Knowledge re-enters the system not as relic, but as future instruction.

The Bridgeworks stands as civilisational architecture.

The Black Continuum and The Bridgeworks are civilisational correction frameworks authored by Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi as part of the Afrodeities canon.

Their purpose is to repair historical rupture by restoring Africa and Black peoples to an unbroken continuum of knowledge, culture, and civilisational contribution.

Evidence for Deliberate Design

African knowledge systems were deliberately designed for rupture because:

Griotic training required decades and overlapped specialists (Hale) - not needed unless engineering for continuity

Ifá remained oral even with access to writing (Bascom) - explicit choice for portability

Nsịbịdị was encrypted by design (Dalby) - protection through illegibility

Cosmograms were portable by design (Fu-Kiau) - "what can be built can be destroyed"

Rhythm was embodied (Chernoff) - "knowledge in the body can't be taken"

Written + oral systems coexisted (Hunwick) - "knowledge shouldn't depend on fragile materials"

Proverbs encode design principles - "a single hand cannot carry a load"

This is not coincidence. This is architecture.

FAQs

Sources & Further Reading for The Bridgeworks

This page synthesizes research across African oral tradition, comparative epistemology, historical methodology, diaspora studies, and civilizational theory. The sources below are organized thematically to support the architectural framework presented here.

Foundational Theory: Civilisational Architecture & Epistemic Systems

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

Theoretical framework for understanding knowledge systems as structured architectures rather than content accumulation.

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

Establishes how knowledge systems operate through paradigms, relevant for understanding African civilisational grammar.

Polanyi, Michael. The Tacit Dimension. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966.

Analysis of embodied and implicit knowledge systems—directly relevant to Band I (Story into Breath).

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Theoretical grounding for centering non-European epistemologies as complete systems, not derivatives.

African Oral Tradition & Transmission Systems (Band I)

Vansina, Jan. Oral Tradition as History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Foundational work establishing oral tradition as systematic, verifiable historical record—supports Griot as custodianship.

Okpewho, Isidore. African Oral Literature: Backgrounds, Character, and Continuity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

Comprehensive study of African narrative systems as engineered knowledge transmission.

Hale, Thomas A. Griots and Griottes: Masters of Words and Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998.

Documents West African griotic systems as disciplined, communally verified memory technology.

Goody, Jack. The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Challenges oral/literate binary—shows oral systems as parallel technologies, not pre-literate substitutes.

Finnegan, Ruth. Oral Literature in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Early comprehensive survey establishing complexity and structure of African oral traditions.

African Writing Systems & Inscription (Band II: Script)

Dalby, David. Africa and the Written Word. Lagos: Centre for Black and African Arts and Civilization, 1986.

Documents indigenous African writing systems including Nsịbịdị, Vai, and others.

Diringer, David. The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind. 3rd ed. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1968.

Places African scripts (including Medu Neter) within global history of writing systems.

Hunwick, John & Alida Jay Boye (eds.). The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Rediscovering Africa's Literary Culture. London: Thames & Hudson, 2008.

Documents Timbuktu manuscript traditions—proof of African written knowledge preservation.

Sass, Benjamin. The Genesis of the Alphabet and Its Development in the Second Millennium B.C. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1988.

Analysis of early alphabetic systems including African contributions.

African Cosmology, Symbolism & Visual Systems (Band II: Sigil)

Fu-Kiau, Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki. African Cosmology of the Bantu-Kongo: Principles of Life and Living. Brooklyn: Athelia Henrietta Press, 2001.

Explains Kongo cosmograms (dikenga) as operational governance and cosmological encoding.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. New York: Random House, 1983.

Traces continuities of African visual/symbolic systems across diaspora.

Drewal, Henry John & Margaret Thompson Drewal. Gelede: Art and Female Power Among the Yoruba. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983.

Documents how Yoruba visual systems encode governance, ethics, and cosmology.

African Material Culture & Architecture (Band II: Memorabilia)

Connah, Graham. African Civilizations: An Archaeological Perspective. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Comprehensive archaeological documentation of African architectural and material achievements.

Phillipson, David W. Ancient Ethiopia: Aksum, Its Antecedents and Successors. London: British Museum Press, 1998.

Documents Ethiopian architectural memory systems (rock-hewn churches, stelae).

Huffman, Thomas N. Snakes and Crocodiles: Power and Symbolism in Ancient Zimbabwe. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1996.

Analysis of Great Zimbabwe as architectural encoding of knowledge.

Garlake, Peter. Great Zimbabwe. London: Thames & Hudson, 1973.

Foundational archaeological study of Great Zimbabwe as civilisational proof.

African Sciences: Mathematics, Time, Ecology (Band III)

Zaslavsky, Claudia. Africa Counts: Number and Pattern in African Cultures. 3rd ed. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1999.

Documents African mathematical systems, including fractal geometry and numerical reasoning.

Eglash, Ron. African Fractals: Modern Computing and Indigenous Design. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1999.

Analysis of fractal mathematics in African architecture, textiles, and settlement patterns.

Mbiti, John S. African Religions and Philosophy. 2nd ed. Oxford: Heinemann, 1990.

Examines African temporal systems (cyclical, spiral time) as cosmological and practical frameworks.

McCann, James. Green Land, Brown Land, Black Land: An Environmental History of Africa, 1800-1990. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 1999.

Documents African ecological knowledge and land management systems

African Metallurgy & Technology (Band III: Technologica)

Schmidt, Peter R. Iron Technology in East Africa: Symbolism, Science, and Archaeology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Documents advanced African iron smelting technologies and their cosmological integration.

Van der Merwe, Nikolaas J. & Donald H. Avery. "Science and Magic in African Technology: Traditional Iron Smelting in Malawi." Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 57, no. 2 (1987): 143-172.

Analysis of African metallurgical expertise as integrated technical and ritual knowledge.

Childs, S. Terry & Eugenia W. Herbert. "Metallurgy and Its Consequences." In African Archaeology, edited by Ann Brower Stahl, 276-300. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005.

Overview of African metallurgical achievements and their civilisational significance.

Diaspora Continuity & Knowledge Survival

Gomez, Michael A. Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Documents how African knowledge systems survived and adapted under enslavement.

Sublette, Ned. The World That Made New Orleans: From Spanish Silver to Congo Square. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2008.

Traces African cultural/knowledge continuities in diaspora urban contexts.

Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Database-driven analysis of African cultural continuities across Atlantic displacement.

Thornton, John K. Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Positions Africans as active agents carrying knowledge systems across diaspora.

Rupture, Resilience & Civilisational Survival

Diop, Cheikh Anta. The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1974.

Establishes African civilisational achievements often erased or misattributed.

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications, 1972.

Documents systematic disruption of African knowledge systems through colonialism.

Eze, Michael Onyebuchi. Intellectual History in Contemporary South Africa. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Analysis of how African intellectual traditions persist despite systematic suppression.

Comparative Epistemology & Knowledge Systems

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. London: Routledge, 2014.

Theoretical framework for understanding suppressed knowledge systems—directly supports Bridgeworks logic.

Harding, Sandra (ed.). The Postcolonial Science and Technology Studies Reader. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

Collection examining non-Western knowledge systems as complete epistemologies.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books, 2012.

Methodological framework for centering indigenous/colonized knowledge systems.

Mythology as Knowledge Technology

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. Structural Anthropology. New York: Basic Books, 1963.

Establishes mythology as structured knowledge system (supports Fable as instruction).

Vernant, Jean-Pierre. Myth and Thought Among the Greeks. London: Routledge, 1983.

Analysis of mythology as civilisational thought—applicable to African mythic systems.

Kirk, G.S. Myth: Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970.

Theoretical framework for understanding myth as functional knowledge encoding.

Bridgeworks Context

This framework synthesizes but extends beyond the above sources. The Bridgeworks is an original civilisational architecture developed by Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi within Afrodeities, positioning African knowledge systems as complete, engineered, and resilient epistemologies designed for survival under rupture.

For specific Bridgeworks components, see individual pillar pages: Fable, Griot, Score, Spell, Script, Sigil, Memorabilia, Soil, Numbers, Time, Technologica, Seed.Chernoff, John Miller. African Rhythm and African Sensibility. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Bascom, William. Ifá Divination: Communication Between Gods and Men in West Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1969.

Carney, Judith. Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001. (for seed storage practices)

Bridgeworks Circle

Mapping African memory through twelve vital functions.

Memory Flow

Tracing how knowledge persists despite erasure.

Knowledge Roots

Exploring the foundations beneath cultural survival.

"The Bridgeworks" is an original civilisational framework developed by Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi within Afrodeities.

Unearthing Africa’s myths, history, and stories together.

© 2024. All rights reserved.

© Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi 2025.

All rights reserved.

The Afrodeities Codex and all associated titles, stories, characters, and mythologies are the intellectual property of the author. Unauthorized use is strictly prohibited.

Goddesses