Aksum: The African Empire the World Forgot

Unveiling the forgotten African empire that shaped ancient global history

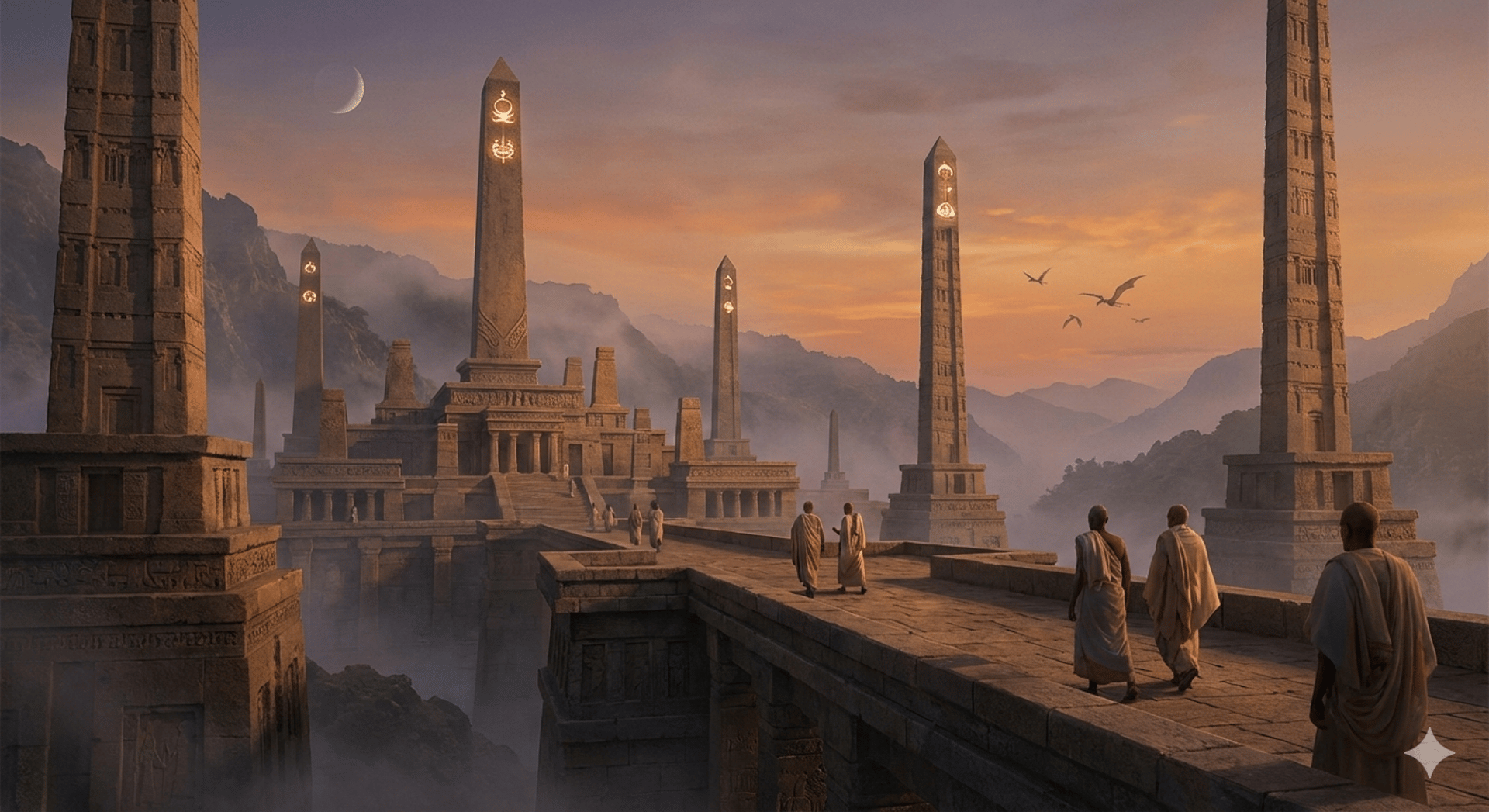

Aksum: The African Empire the World Forgot

by Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi

In the third century CE, a Persian philosopher named Mani listed the four greatest empires in the world. He named Rome, Persia, China, and Aksum. Not Greece. Not Babylon. Not any European state. Aksum, in the highlands of what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, governed the Red Sea trade routes, minted its own coinage, corresponded with Constantinople as a sovereign equal, and produced a written literature in its own script. The fourth power in the world, in the reckoning of a man who had reason to know, was African.

This fact has not found its way into the standard account of the ancient world that is taught in Western schools. The standard account has room for Rome, some for Persia, less for China, and essentially none for Aksum. The omission is not accidental. A world in which Africa sits at the table of the great powers of antiquity as a full and acknowledged participant is a different world from the one that the history of the last five centuries requires.

What Aksum Was

The Aksumite Empire emerged in the first century CE from the highlands of the Ethiopian plateau, drawing on a tradition of statehood that predated it by several centuries in the form of the kingdom of D'mt and the South Arabian influences that reached the region across the Red Sea. By the third century it had become the dominant power on both shores of the Red Sea, controlling the trade routes between the Mediterranean world, Arabia, India, and the interior of Africa. Its port of Adulis, on the Eritrean coast, was one of the most important commercial hubs in the ancient world.

The wealth that flowed through Adulis, the ivory, gold, obsidian, slaves, and exotic animals that the empire exported, and the cloth, metal, wine, and olive oil that it imported, made Aksum prosperous enough to build at a scale that still astonishes. The stelae, the giant obelisks that the Aksumites quarried from single pieces of granite and raised as royal monuments, are engineering achievements whose execution required a sophisticated understanding of stone working, of leverage and counterbalance, and of the organisational capacity to move monolithic objects weighing hundreds of tonnes across miles of difficult terrain. The largest stele ever raised at Aksum, now collapsed, would have stood thirty-three metres. It is the largest single piece of stone that any ancient civilisation attempted to erect.

The Script and the Faith

Aksum produced the Ge'ez script, an alphasyllabary developed from earlier South Arabian writing systems and refined into a distinctive African written language that became the vehicle for an extraordinary literary tradition. Ge'ez is still used today as the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Church, a direct continuity of written African culture stretching back nearly two thousand years.

The adoption of Christianity by the Aksumite king Ezana in the fourth century CE, around 330 CE by conventional dating, made Aksum one of the first states in the world to adopt Christianity as its official religion, predating the Christianisation of most of Europe. The Ethiopian Orthodox tradition that descends from that conversion is one of the oldest continuous Christian traditions in the world, preserving practices, texts, and artistic forms that the European churches diverged from long ago. The Ark of the Covenant, which Ethiopian tradition holds to be in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Aksum, is a claim that the Ethiopian church has maintained without interruption for fifteen centuries. Whether or not the claim is literally true, its persistence is evidence of the depth and confidence of a civilisational tradition that has never doubted its own antiquity or its own significance.

Coinage and Correspondence

The minting of coins is one of the clearest markers of state sophistication in the ancient world. It requires a reliable supply of metal, the technical capacity to produce consistent dies, the administrative infrastructure to distribute and regulate currency, and the international recognition that makes the coins acceptable in trade beyond the empire's borders. Aksum minted gold, silver, and bronze coins from the third century CE onward, with inscriptions initially in Greek, the lingua franca of Mediterranean trade, and later in Ge'ez. The coins bear the names and images of Aksumite kings, are found in archaeological sites from India to the Mediterranean, and are collected today in museums across Europe and the Middle East as evidence of a sophisticated ancient economy.

The letters preserved from Aksumite kings to Roman emperors and Egyptian rulers show states treating each other with the careful protocol of equals. When the Roman emperor Constantius II wrote to the Aksumite king Ezana in the fourth century to request the extradition of a Nicene Christian bishop who had fled to Aksum, he addressed him with the full diplomatic courtesy due a sovereign of equivalent standing. Ezana declined. The correspondence is evidence not only of Aksumite power but of the international recognition of that power by the most powerful state in the Western world.

What Was Looted and What Endures

The Aksum Obelisk, the second largest of the stelae that still stand at Aksum, was looted by Mussolini's forces in 1937 following the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, cut into five pieces for transport, and erected in Rome as a monument to Italian imperialism. It stood in Rome for nearly seventy years. Italy agreed to return it in 1947 under the terms of the post-war peace treaty and did not actually do so until 2005, when the pieces were flown back to Ethiopia and re-erected at Aksum. The delay of fifty-eight years required considerable diplomatic pressure and reflects the reluctance with which stolen African cultural property is returned even when the legal obligation to do so is clear.

The endurance of Aksumite civilisation in the Ethiopian state, in the Orthodox church, in the Ge'ez script, and in the physical monuments that survive is evidence of a continuity that most ancient empires cannot claim. Rome is ruins and a modern state that largely ignores it. Aksum is still present in the living culture of a nation that has maintained its independence against colonial conquest. Ethiopia was the only African country to successfully resist Italian colonisation in 1896, defeating the Italian army at the Battle of Adwa in a victory that sent a shock through the European imperial project and made Ethiopia a symbol of African dignity and resistance for the entire continent and its diaspora.

The fourth great power of the ancient world never entirely disappeared. It simply waited for the world to remember.

This article is part of the If Africa Ruled The World codex, a canon of corrective African civilisational history developed by the Afrodeities Institute. Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi is a mythologist, scholar, and author of Nigerian Mythology: The Shadow Sky. Enquiries from editors, programmers, and conference organisers are welcome at afrodeities.org.

Related reading: Kemet: Ancient Egypt Was African. The Swahili Coast: Africa's Ocean Empire.

"The Bridgeworks" is an original civilisational framework developed by Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi within Afrodeities.

Unearthing Africa’s myths, history, and stories together.

© 2024. All rights reserved.

© Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi 2025.

All rights reserved.

The Afrodeities Codex and all associated titles, stories, characters, and mythologies are the intellectual property of the author. Unauthorized use is strictly prohibited.

Goddesses