The Swahili Coast: Africa's Ocean Empire

Unveiling the rich history of the Swahili Coast's vibrant trade network

The Swahili Coast Story

by Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi

The Indian Ocean is not a European sea. This seems obvious and yet it requires stating, because the story of global trade is so thoroughly told from a European perspective that it is easy to absorb, almost without noticing, the assumption that the ocean was opened, mapped, and made commercially significant by the Portuguese in the fifteenth century, when Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope and arrived on the East African coast in 1498. Da Gama arrived to find a network of city-states, trade routes, navigational charts, commercial relationships, and maritime infrastructure that had been operating for centuries without him. He hired an African and Arab pilot to guide him across the Indian Ocean to India. The route was already known. The ocean was already mapped. The trade was already running.

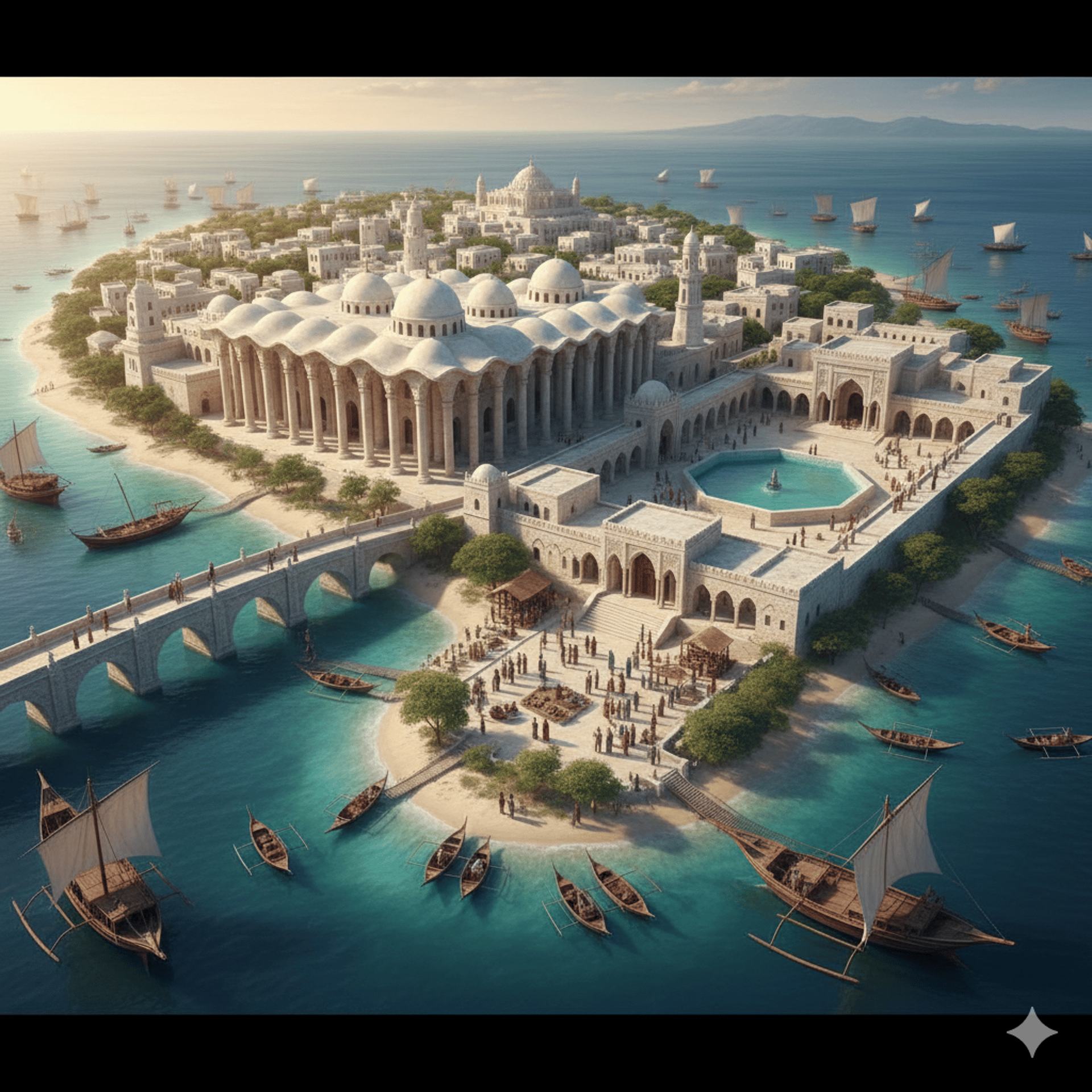

The Swahili Coast, stretching roughly two thousand kilometres from present-day Somalia in the north to Mozambique in the south, was the western shore of an Indian Ocean trading system that connected Africa to Arabia, Persia, India, and China in a web of commercial and cultural exchange that made it, between roughly the eighth and sixteenth centuries, one of the most cosmopolitan and economically significant regions in the world. The civilisation that developed along this coast was African. It was also, by virtue of its deep integration with the broader Indian Ocean world, one of the most internationally connected African civilisations in history.

The City-States

The Swahili Coast was not a unified empire. It was a network of independent city-states, each one controlling its own stretch of coast and its own relationships with the interior trading networks that brought gold, ivory, iron, and enslaved people down to the coast, and with the ocean-going traders who arrived with cloth, porcelain, glass beads, and metalwork from across the Indian Ocean world. The major cities, Kilwa Kisiwani, Mombasa, Malindi, Zanzibar, Pate, Lamu, Sofala, were governed by their own rulers, competed with each other for trade advantage, and occasionally formed alliances or fought each other, but shared a common culture, a common language in Swahili, and a common identity as people of the coast.

Kilwa Kisiwani, on an island off the southern coast of present-day Tanzania, was at its height in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries the wealthiest city on the Swahili Coast and, by many accounts, one of the wealthiest cities in the world. It controlled the gold trade from the Zimbabwe plateau, receiving the metal through the inland trading networks and exporting it northward to Malindi and Mombasa and from there across the ocean. The fourteenth-century Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta, who visited Kilwa in 1331 and who had travelled extensively across the Islamic world from Morocco to China, described it as one of the most beautiful cities in the world and praised the generosity and piety of its sultan, Abu al-Mawahib, whose name means father of gifts, a ruler celebrated for his almsgiving and his patronage of scholars.

Building in Coral Stone

The architecture of the Swahili city-states, which survives in ruins along the coast and in the living fabric of cities like Lamu and Stone Town in Zanzibar, represents a distinctive African architectural tradition shaped by the materials available and by the aesthetic and functional requirements of a society deeply engaged with maritime trade. The primary building material was coral stone, cut from the reef and shaped into blocks that were mortared with lime made from burned coral. The buildings that resulted, the mosques, the palaces, the merchants' houses with their elaborate carved doorways, were suited to the coastal climate, cool in the heat, resistant to the salt air, and built to a scale and refinement that reflected the wealth of the cities they housed.

The Great Mosque of Kilwa, built and expanded between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries, is the oldest standing mosque in sub-Saharan Africa. Its barrel-vaulted roofs, its forest of columns supporting a ceiling of coral domes, its careful orientation toward Mecca, represent a local architectural tradition that absorbed influences from the broader Islamic world and transformed them into something distinctly of the coast. The Husuni Kubwa palace complex, built by Sultan al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman in the fourteenth century, was at the time of its construction one of the largest buildings south of the Sahara, with a great octagonal swimming pool, a market area, audience halls, and residential quarters arranged around courtyards in a plan that reflects both Islamic palatial architecture and the practical requirements of a ruler who governed a trading state.

The Chinese Connection

The depth of the Swahili Coast's integration into the Indian Ocean trading system is perhaps most dramatically illustrated by its connections with China. Chinese porcelain has been found in archaeological sites along the coast in quantities that reflect not occasional contact but sustained commercial relationships. The famous voyages of the Chinese admiral Zheng He, which brought an enormous fleet of Chinese treasure ships into the Indian Ocean between 1405 and 1433, included visits to the Swahili Coast. The Malindi sultan sent a giraffe back to China as a diplomatic gift in 1415, an event recorded in Chinese court annals with wonder at this strange and magnificent creature that seemed to fulfil the description of the mythical qilin, a creature of good omen. The giraffe arrived at the imperial court in Nanjing and was received as a sign of heaven's favour.

The exchange was not merely exotic. It was commercial and diplomatic, conducted by states that recognised each other as worthy partners. The Swahili rulers who corresponded with the Ming court were not supplicants. They were sovereign rulers with something to offer and something to gain, participants in a system of international exchange that was organised, sustained, and on the African side, African-led.

What the Portuguese Did

Da Gama arrived on the Swahili Coast in 1498 and encountered a level of sophistication that unsettled him. He also encountered resistance from city-states that correctly identified his intentions as hostile. The Portuguese response to that resistance, developed over the following decades, was systematic violence. They bombarded coastal cities, destroyed the dhow fleets that carried the trade, established fortified positions at strategic points along the coast, and inserted themselves as violent intermediaries into a trading system they had not built and could not sustain on the same terms.

The Portuguese did not replace the Swahili trading system. They disrupted it, extracted from it, and damaged it severely before their own power waned and the city-states began to recover under new political arrangements in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. What they could not do was erase the evidence of what had existed before them. The coral stone ruins still stand. The Chinese porcelain is still in the ground. Ibn Battuta's account is still legible. The Indian Ocean remembers the ships that crossed it long before any European sail appeared on its horizon.

Because of the lies we were taught, large parts of this history are obscured, and it is more important than ever that more of us know these stories.

This article is part of the If Africa Ruled The World codex, a canon of corrective African civilisational history developed by the Afrodeities Institute. Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi is a mythologist, scholar, and author of Nigerian Mythology: The Shadow Sky. Enquiries from editors, programmers, and conference organisers are welcome at afrodeities.org.

Related reading: Great Zimbabwe: Who Really Built It. Aksum: The African Empire the World Forgot.

Heritage

Echoes of centuries-old trade and culture on Africa’s coast

FAQs

What is the Swahili Coast?

A historic region along East Africa's Indian Ocean shoreline rich in trade and culture.

Who controlled the Indian Ocean?

Long before Europeans arrived, local city-states and traders managed vibrant maritime networks.

Did Vasco da Gama discover this region?

No, he arrived to an already thriving network of cities, trade routes, and maritime expertise.

What languages were spoken here?

Swahili, Arabic, and various African languages shaped the region’s rich cultural tapestry.

Why is this history important?

It challenges Eurocentric views and highlights Africa’s role in global trade history.

How can I learn more about the Swahili Coast?

Explore historical texts, local stories, and archaeological findings that reveal its rich past.

"The Bridgeworks" is an original civilisational framework developed by Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi within Afrodeities.

Unearthing Africa’s myths, history, and stories together.

© 2024. All rights reserved.

© Chinenye Egbuna Ikwuemesi 2025.

All rights reserved.

The Afrodeities Codex and all associated titles, stories, characters, and mythologies are the intellectual property of the author. Unauthorized use is strictly prohibited.

Goddesses